I have both a KX2 and a KX3 and they are both fantastic radios. I have the internal battery and charger options offered for both of those radios. The 3S LiPo battery and internal charger combination used in the KX2 to be great. I find the NiMH batteries of the KX3 with the output power limit of 5W coupled with the “manual” internal charging to not be ideal. I have already done a mod to allow the use of LiFEPO4 14500 battery cells but the issue of removing the batteries to charge them is still a pain. (Link to that mod) I have also looked into an internal LiPo battery mod where you use the same battery used with the KX2 but that modification had a cable hanging out of the radio for external charging. That same cable was then plugged into the radio’s 9-15V DC jack to power the radio. (Link to this mod).

Implementing those modifications helped solidify what I desired for my KX3. That is an internal LiPo battery that is charged internally from the EXT DC jack just like the KX2.

Design: I would rather not have an unproven design that could cause RFI or riskily charge the battery while inside of the KX3. The KX2 internal battery charger (p/n KX2IBC) paired with the KX2 internal battery (p/n KXBT2) is a proven safe design that is RF quite. I went down the rabbit hole of creating PCB that “repackages” the KX2 internal charger circuit into a form-fit that will fit in the KX3.

I did not spend too much time investigating implementing the RTC functions in my PCB. Once I realized the KXBC3 board uses a custom programmed PIC chip, I moved onto focusing on repackaging the charging circuit. Additionally, since the same PIC creates the battery monitoring data for the KX3, I opted to not try and replicate the battery monitoring signals in my design. The battery voltage will be reported as the power supply voltage.

Space: The AA battery holders as well as the KXBC3 PCB need to be removed to make room for the 3S LiPo battery. The KXBC3 provides the NiMH charging circuits as well as the Real-Time Clock functionality. The NiMH charging will clearly not be needed after my modification, but what about the RTC functions. I did not spend too much time investigating implementing the RTC functions in my PCB. Once I realized the KXBC3 board uses a custom programmed PIC chip, moved onto focusing on repackaging the charging circuit. I would use Steve Gollub’s (DL9TX) 3D print designs as starting point for my effort.

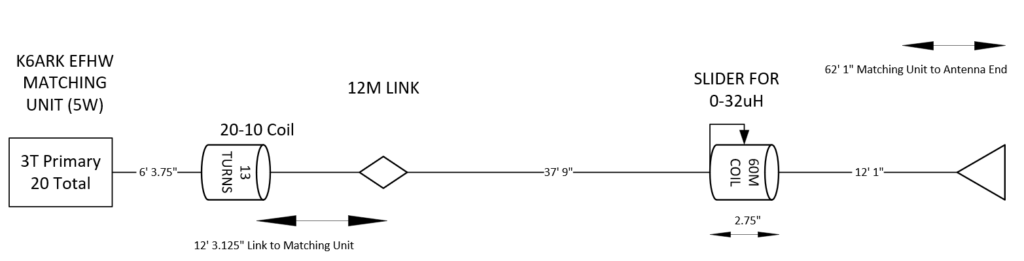

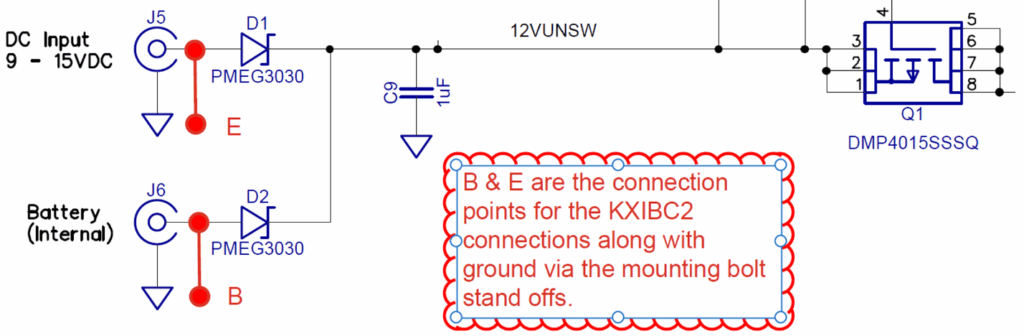

Merging the KX2 design into the KX3.First let’s look at the KX2 design, The charging functionality of the KXIBC2 board basically has three connections: Ground, external power and the battery connection. D1 and D2 provide the “OR” function that has the radio drawing power from whichever source as the higher voltage.

The E and B connections for the KXIBC2 design can be easily replicated in the KX3. The KX3 does not have the “OR” functionality between the external and battery sources. That can be replicated on the PCB design.

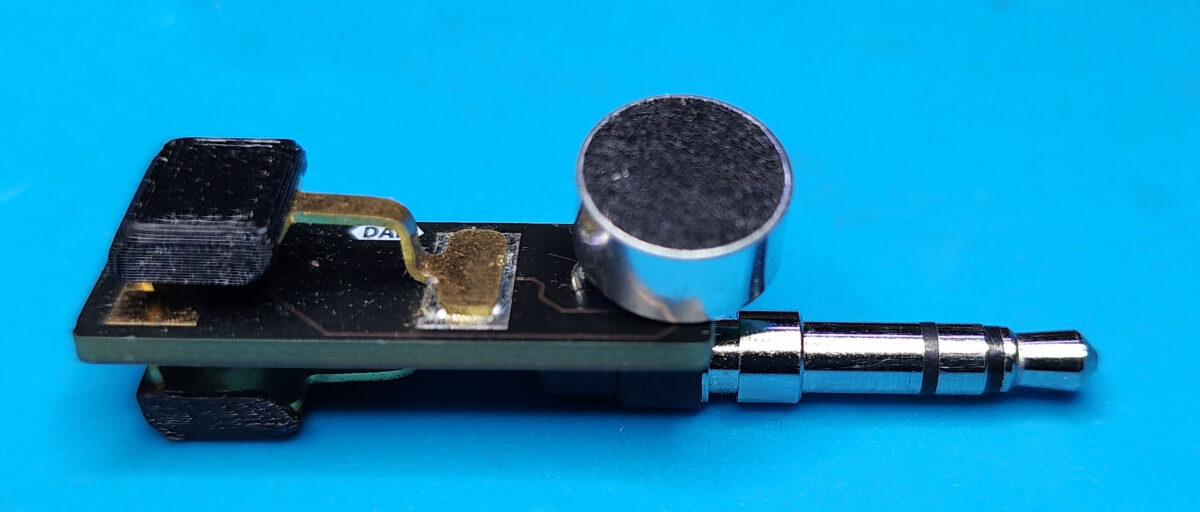

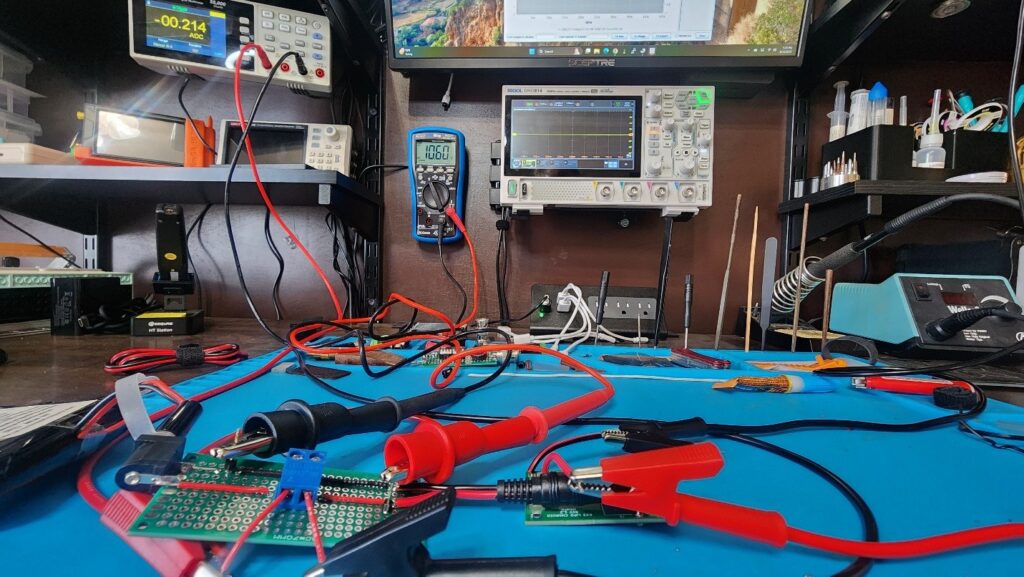

Fast forwarding through the whole KiCad PCB design and prepping, I got the board sent for fabrication and before long I had some prototype boards in from the PCB manufacturing house. Time for some testing.

Testing and Modifications of the Design

I made a solder up bread board that that would be in line with the charger PCB and the battery. From here I could monitor both the current and voltage to the battery. The two multimeters were also connected to my bench computer so the data could be logged off. During the first tests I discovered I have selected the incorrect diodes to be installed by the PCB house. Diodes D3.1 and D3.2 were supposed to be BAV70-5 but I picked BAV70-6. The big difference there is the diodes are reversed internally…Dooh! <Yeah, that is why we test> While waiting for the updated parts, I decided that the 220-250ma charge rate was extremely conservative for a 2600mah battery. R1 in conjunction with Q1 and Q6 sets the maximum charge current. Here is the description from the KX2 manual.

Q1 and Q6 is a current limiting circuit. Current is largely set by the voltage drop across R1 equaling the drop across the base-emitter junction of Q6. As current increases past this point, Q6 collector current also increases, shunting Q1 base current through Q6, and reducing the current through Q1. Actual current will be somewhat dependent on the voltage differential across Q1, being slightly higher when charging starts, and decreasing as charging nears completion.

Using one of my other boards as a donor, I put another 3.3 ohm resister in parallel with R1 to create at 1.65-ohm resistor network. This lower resistance will require twice as much current to produce the emitter-base saturation voltage of Q6 (0.95V) which sets the limit current.

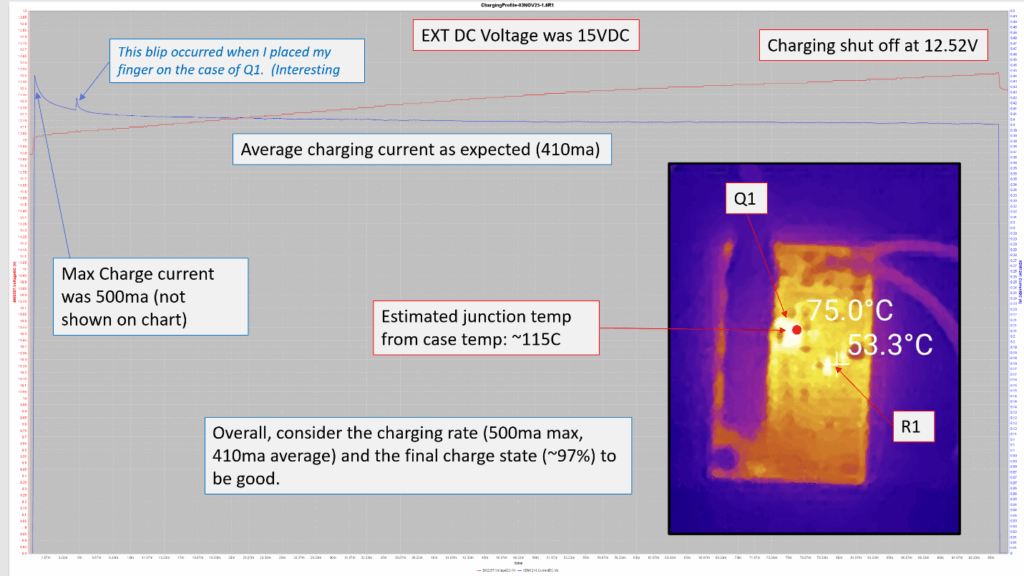

With the proper diodes installed the next round of testing showed an initial charge current around 480ma that quickly settled into 410ma. This equates to charge rate of about C/6 or C/7. The charging stopped at the advertised/expected at cutoff voltage of 12.43VDC. Within seconds this settled down to the open circuit voltage of 12.25VDC

At this point, I was extremely happy with the charging rate, but I wanted to optimize the charge cutoff voltage to get the final charge a little closer to 100%. The voltage divider network of R2 and R6 provide the scaled representation of the battery voltage to the comparator U1. Increasing the value of R2 or decreasing the value of R6 would lower the voltage at their junction which U1 uses to determine when to shutoff the charge circuit. The current value of R2 was 133K. A value of 134.6K should raise the charge rate to 98%. 134K SMD resistors are hard to come by, so I sourced a 135K resistor.

Testing with the new R2 value of 135K resulted in charging cutting off at 12.53V. This surface charge voltage equates to about 97% charge. As expected, the open circuit voltage settled in at 12.41V. I was very happy with those results.

The final modification was to swap out the two parallel 3.3-ohm resistor network that make up R1 to a single 1.6-ohm resistor. The 1210 resisters are rated at 500mW. This is no where close to an issue with the two 3.3 ohm resistor in parallel but the single 1.6 ohm resistor is closer to its max rating. Even if the charge current was 500ma the power would within the resistor’s rating (.500A * 0.95V = 475mW).

The next rounds of testing added the use of thermal camera to monitor the PCB. The results of those tests showed R1 to be well within thermal limits and below it derating threshold value. Q1 was interestingly hot with a maximum case temperature of 77C and an average case temperature 75C over the charge cycle when the external charge voltage was at the maximum of 15VDC. The die junction temperature is estimated to about 115-125C. The datasheet lists a maximum die temperature rating of 150C so it closer than I would prefer but is acceptable. When charged at the typical vehicle and ham shack voltage of 13.8VDC, Q1 averaged over 15C cooler over the entire charge cycle. (If I do further revision to this PCB, I’ll look to improve the heatsinking of this component)

My intended charging method is use my 13.8VDC from my base station power supply when at home and to use a 15VDC USB-PD cable and a power bank when away from home.

Installation

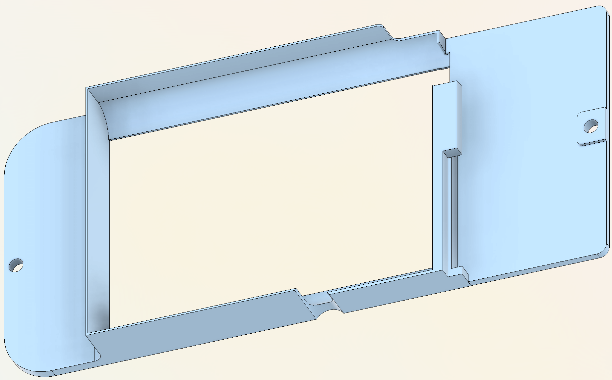

I modified the Stefan Gollub Li-Ion battery holder design quite a bit. The retainer board, that replaces the stock KX3 charger board/NIMH battery retainer, was modified to also replace one of the PCB standoffs by incorporating into the retainer. This increased the space for the battery by 1.5mm. His battery holder design was heavily modified to also house the charger PCB. It was also optimized for better vertical clearance for the battery.

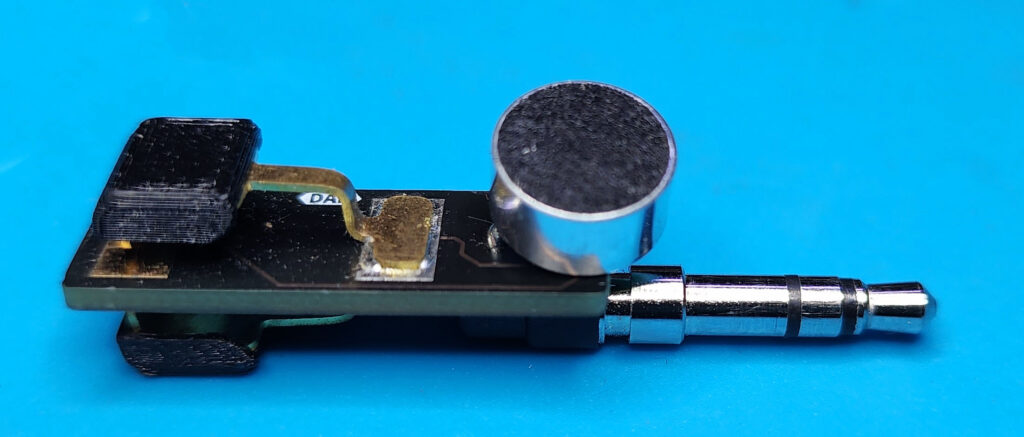

Figure 12 – Completed Mod

The charge LED on the PCB can be seen through the opening in the case for the external DC jack with most DC barrel plugs, but you have to look at just the right angle. I do not have a 2M transverter module in my KX3 so I was able to reutilized that antenna jack opening to mount and LED to provide charge indication.

Overall, I’m quite happy with how this project turned out. I have taken the KX3 out on couple of activations already and it is nice to have 10 watts at the ready. Also super nice to just plug it in and let in charge when you get home. Many thanks to Stefan Gollub’s (DL9TX) for his 3D model designs which spurred on my ideas with this project.

Here is a PDF version of this post